Part of Our Ongoing Series About Folks Who Achieved Great Things Later in Life

Art has never really been my thing. Art class was always my weakest subject in school, and there just wasn’t much about it that interested me. Sure, I knew that Leonardo da Vinci painted the Mona Lisa; that Michelangelo sculpted David; and that Vincent van Gogh misplaced an earring or something…but that was about the sum of my knowledge. Oh, and of course Charles Schulz drew Snoopy and Charlie Brown.

It’s not so much that I found art boring as it is that there were so many other things — birds, music, history, the Green Bay Packers — that were more exciting…at least for me. The fact that I couldn’t draw straight stick people if my life depended on it didn’t help much either.

But that all changes now, because today we’re going to talk about the fascinating life and works of “The Father of Modern Art,” Paul Cézanne. A true artistic giant, he was largely unknown and unappreciated in his younger years. Once his life and career entered the home stretch, though, Paul Cézanne utterly transformed the world of art.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Early Life

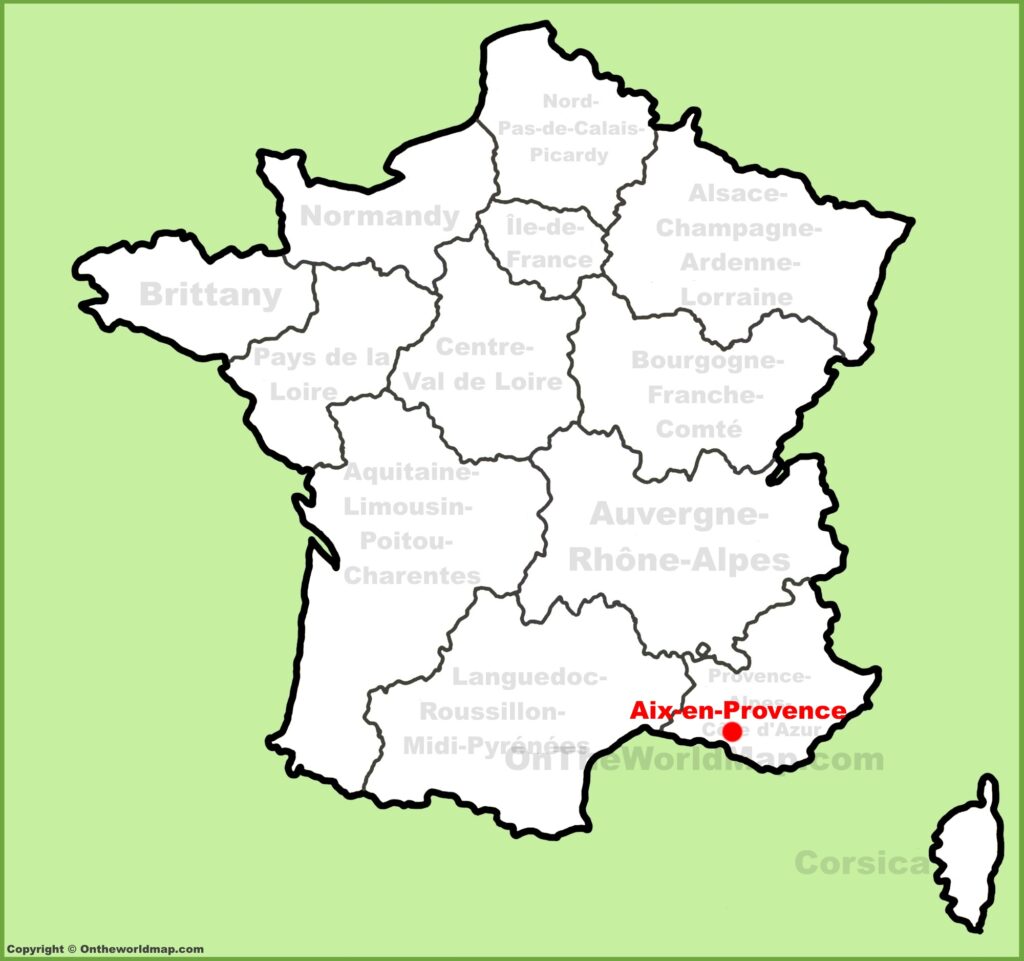

In the foothills of the French Alps, about 20 miles north of Marseille, lies the ancient, historic and picturesque small city of Aix-en-Provence. It was here that Paul Cézanne was born to a relatively affluent family in 1839. His father was a successful banker who hoped his son would study law or become a successful businessman. Paul’s interests lay elsewhere, however, as he loved to draw and paint from an early age.

At age 13, Cézanne was enrolled in the Collège Bourbon secondary school. It was there that he met the writer and activist Émile Zola, who would become his lifelong friend. In compliance with his father’s wishes, he enrolled in law at the University of Aix-en-Provence at age 20.

He managed to stick it out for two years, but Cézanne’s heart was never in legal studies. He soon enrolled in night art classes and began neglecting his law curriculum. Eventually, he abandoned jurisprudence altogether, much to his father’s disapproval

Art Education

His father was even more unhappy when — encouraged by his friend Emile Zola — Cézanne left for Paris at age 22 to follow his dream and study art. As was often true in his early life, however, things did not go well there. His application to the renowned École des Beaux-Arts was rejected, and the disappointed and depressed young artist even moved back home to work at his father’s bank for a time.

The siren call of the artistic life was too strong, however, and within a year he was back in Paris. Again he made application to the École des Beaux-Arts and again was denied.

Image By Unknown Photographer- Public Domain,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=596637

Undeterred, Cézanne enrolled in the free Académie Suisse. It was there that he met the Impressionist painter Camille Pissarro, who would become his mentor, as well as young artists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

Early Career Frustrations

Paul Cézanne’s early professional career was marked by frustration and disappointment. His father remained unhappy with his chosen career and would provide barely enough resources for Paul to survive, much less thrive. His work was consistently rejected by the venerable Salon de Paris. Even the Salon des Refusés — which displayed art rejected by the official Salon — denied his submissions every year from 1864 to 1869.

For years, Cézanne achieved little recognition and even less financial success as an artist. He faced strong criticism from some of his fellow artists for his unconventional style and felt alienated from much of the art establishment. His health was often poor, with a list of maladies that included chronic bronchitis, vision problems, severe migraines and tuberculosis. His self-doubts grew with every setback.

Painting is a highly solitary art to begin with, and some of Paul Cézanne’s personality traits and work habits likely exacerbated his struggles with interpersonal and professional relationships. Cézanne was introverted and a meticulous perfectionist with a tendency towards extreme self-criticism. At times, the criticism and disdain spilled over specifically to the works of other artists and generally to the entire Impressionist movement. (Notably, nowhere in Dale Carnegie’s seminal “How To Win Friends and Influence People” is mention made of the leadership and influence secrets of Paul Cézanne.)

Cézanne long held the art world establishment in low regard; and the feeling was more than mutual from Impressionism’s painting pooh-bahs, practitioners and peons. He became more and more withdrawn, retreating at one point to his hometown — Aix-en-Provence — to get away from the Paris art scene.

Genesis of a Genius

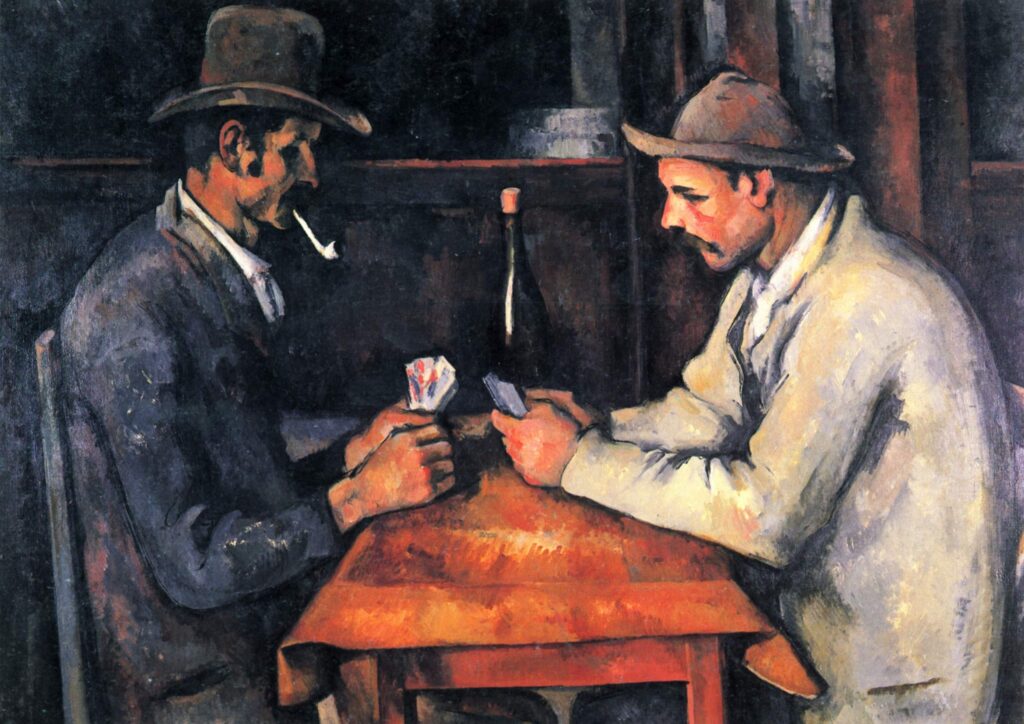

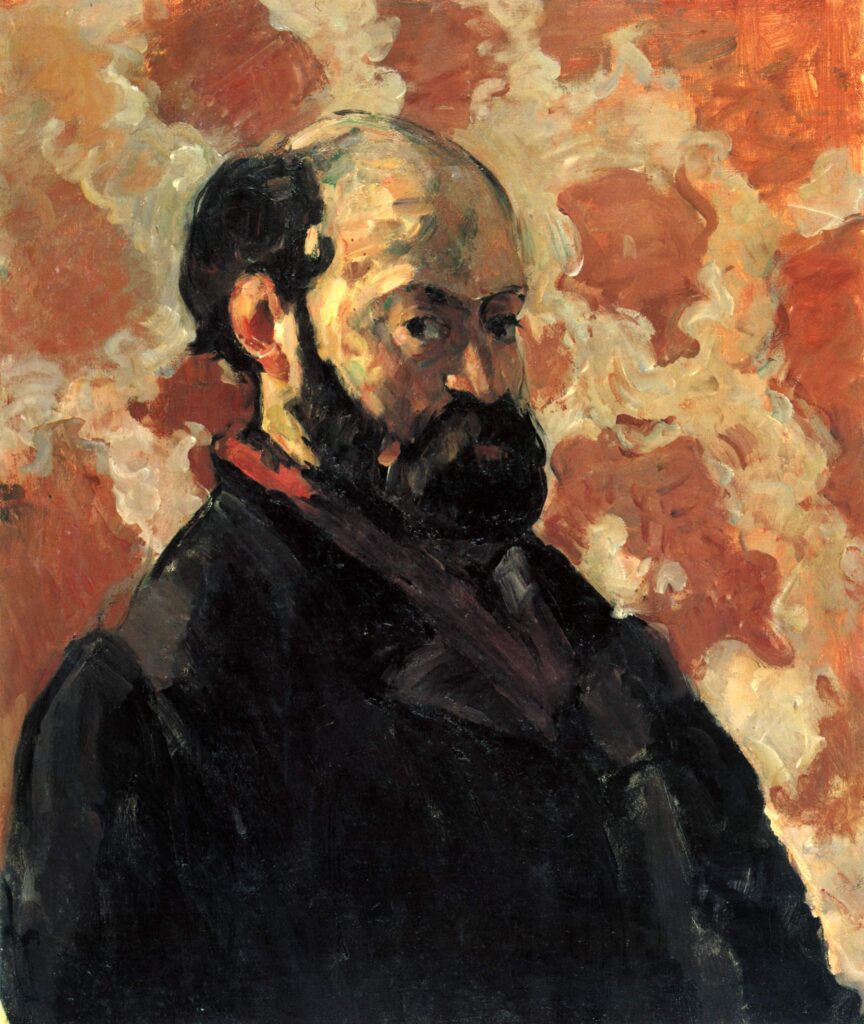

During this period of isolation, Cézanne began to experiment and develop his own unique style. He largely abandoned the illusionistic techniques of his contemporaries, where the illusion of three-dimensional space appears within the painting. With the growing prevalence of photography, Cézanne didn’t want his art to look like something a camera could do. Instead, he embraced a more analytical approach that frequently combined painting with drawing and used color and context to guide the viewer’s eye through the painting into the objects he portrayed.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=26704341

Cézanne’s use of bold brushstrokes, vibrant colors, and geometric forms set him apart from what had come before, and would eventually change art history.

Paul Cézanne’s father never did encourage or embrace his son’s career as an artist, but after a few years he no longer actively opposed it either. The relationship seems to have been somewhat strained without being openly hostile. As Paul approached his 40th birthday, his father passed away — leaving to his son in death what he never did in life, a small fortune that would allow Cézanne the financial freedom to pursue his art for the rest of his days. When his mother passed away a few years later, he inherited the family estate.

Image By Bjs – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=73430761

Recognition and Respect – Finally

As Cézanne approached 50, his career finally began to take off. He began his series “The Bathers” in 1874 and continued working on it for the rest of his life. Its use of symmetrical dimensions was ground-breaking, and it came to be regarded as one of the very first true masterpieces of modern art.

At age 60, Cézanne participated in the Salon des Indépendants, an exhibition showcasing avant-garde artists. Shortly thereafter, his work was featured at the prestigious Exposition Universelle in Paris. By then, the art world was beginning to take notice.

Then came the tour de force…

When the 1904 historic Société du Salon d’Automne exhibition opened at the Grand Palais des Champs-Élysées, an entire room was dedicated to Paul Cézanne, with thirty-one works, including various portraits, self-portraits, still lifes, flowers, landscapes and his famous bathers.

It was the pinnacle of success during his lifetime. Within a few years, Cézanne’s health began to rapidly deteriorate and in 1909 he passed away at the age of 70.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

So there you have it. Paul Cézanne loved to paint from early childhood, but found little support or success for many, many years. Even though he experienced periods of anxiety and depression as the years went by, however, Cézanne’s dedication to his craft never wavered. And when the curtain rose on his final act, it was one for the ages. Today, Paul Cézanne is celebrated as a fearless and groundbreaking pioneer, and honored as the Father of Modern Art. His story is an inspiration to us all.

By Steven Roberts