Talking About the Bird That’s Much More Than Just an Annoying Feature On Your Grandmother’s Clock

Image By Andy Reago & Chrissy McClarren – CC BY 2.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=37123269

This week included the first day of April, providing us the perfect opportunity to learn about the bird whose very name can be synonymous with “fool.” With anywhere from 125 to 150 species world-wide — depending on the source and definition — we’re going to considerably narrow our focus to the US, where three species can be found: the black-billed cuckoo, which is the most common; the mango cuckoo, found only in Southern Florida; and, the star of today’s column: Coccyzus americanus — the yellow-billed cuckoo.

And in fact, there’s so much to talk about when it comes to cuckoos that we’re going to tell the story in two parts. Part One — which you’re reading right now — will cover some more general aspects of cuckoos world-wide (some of which are in stark contrast to the yellow-bill) as well as the geographic range of the yellow-billed cuckoo and where birdwatchers should look for it. Part Two will cover things like size and appearance; sexual dimorphism; diet; conservation status; and, mating, nesting and breeding habits.

So pull up a chair, grab your cocoa-puffs and let’s talk about this mentally eccentric feathered friend.

So. Are They Crazy?

First off, we don’t really use “crazy” to describe people anymore and — with the possible exception of barn swallows during breeding season (they’re just plain psychotic) — in these parts we don’t apply it to birds either.

Image By Bettina Arrigoni – Smith Oaks, TX| — CC BY 2.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=75176414

So, I’m using “mentally eccentric” until something more clever occurs to me. And are they? Simple answer: Nope. They’re just as level-headed as any other of our other avifauna.

So Why the Bad Rap?

Sources differ on just why the word “cuckoo” came to mean “mentally eccentric.” Its popularization undoubtedly occurred mostly in American English, where this particular meaning of the word started to appear in dictionaries around 1918. Its application dates back much farther, however, with at least one instance dating from the 1580s.

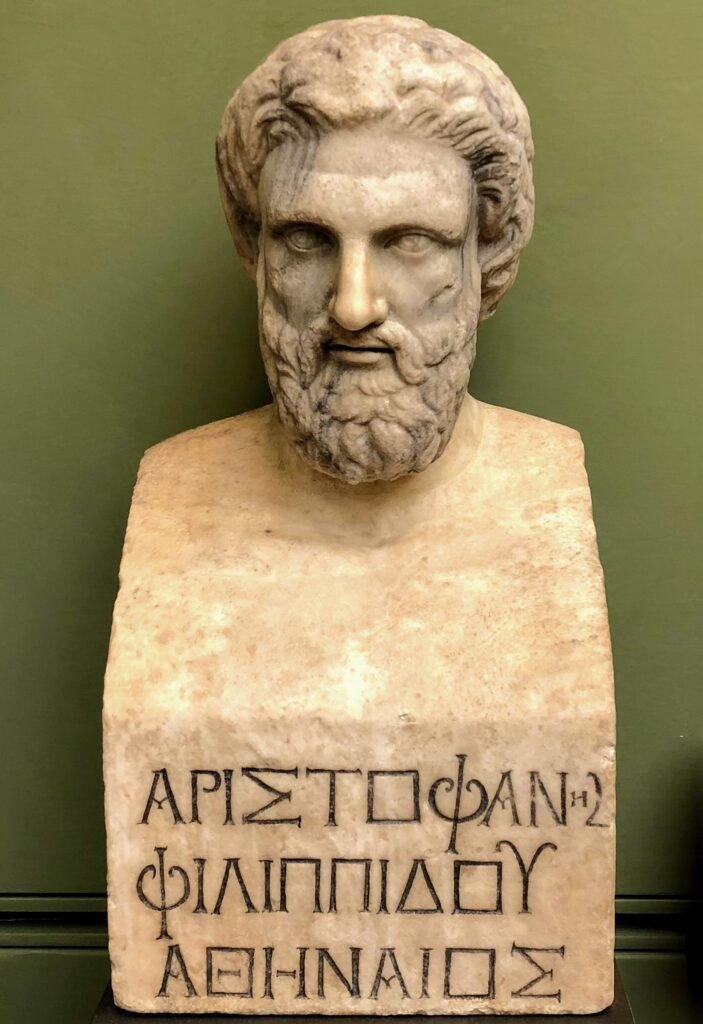

Blame the Greeks?

And if we abandon English for a moment, it really goes back. In 414 BC, Greek playwright Aristophanes created an absurdly — even foolishly — idealistic utopia in the clouds for his play “The Birds.” He named it Νεφελοκοκκυγία or Nephelokokkygia, which translates as “Cloud Cuckoo Land.” So even the ancient originators of philosophy and democracy may have thought there was something not quite right about our friend the cuckoo.

Image By Alexander Mayatsky – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=94123897

That’s the “when,” but we still haven’t answered the “why.” There are two possible answers: one related to vocalizations and the second to some rather ill-mannered nesting behavior. Please note that our own American yellow-billed cuckoo does not typically engage in either offense and frankly is unfairly maligned thanks to the miscreant behavior of its European cousins, the common cuckoo.

Image By Mike McKenzie – Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=41174119

Musical Monotony

The “song” of Europe’s common cuckoo is basically the same two notes — which actually do sound like “cuckoo” — repeated over and over and over again. Even if the bird itself isn’t a little “touched,” listening to its uninspired, repetitive racket for any extended length of time could cause any human to question their own sanity.

In contrast, the song of the yellow-billed cuckoo is a deep, hollow, rhythmic, cascading pattern of notes delivered at a steady pace, with a slight pause between each series. The song can last for several seconds, and the number of repetitions can vary. The overall effect of the song is a distinctive and somewhat melancholic sound.

Here’s a sample:

Taking Absentee Parentism to the Next Level

Then there’s the incredibly lazy, irresponsible — not to mention neglectful — parenting technique of the common cuckoo referred to as “obligate brood parasitism.” Not to be bothered with incubation duties — much less caring for hatchlings — nearly 50 species of Old World cuckoos will sneakily lay their eggs in the nests of other birds and leave the parenting up to them.

The European common cuckoo is just devious enough to know which birds have longer incubation periods and select their nests as “foster homes.” The cuckoo’s eggs thereby hatch first. And are the cuckoo hatchlings just grateful to have a comfortable, safe home to share with their substitute family? Oh, heck no. When the host parents bring food, the interlopers are not about to share it with any would-be foster siblings.

With audacious effrontery, the young cuckoo pushes the competing eggs onto its own back, one by one. It then braces its feet on the sides of the nest and rolls each egg over the edge. Splat! (How rude, right?)

The Part That Really Bugs Me

But it needs to be said that the unwitting host birds aren’t winning any “Parent of the Year” awards, either. The favorite targets of the common cuckoo are flycatchers, chats, warblers, pipits and buntings, and these have got to be the most clueless birds on the planet. First, they’re not paying enough attention to notice that a bird from entirely different species dropped by; tossed out one of the eggs that was there and laid one of its own; and, then flew off without so much as a “thank you” or an “I need a favor.”

Twelve days later, the cuckoo hatches and promptly eliminates any other eggs or hatchlings. For the foster parents, though? It’s just business as usual. It never occurs to them that they had five eggs but now only one hatchling in the nest. At no point does Mr. Bunting say to Mrs. Bunting: “Have you noticed that Junior is twice my size and doesn’t look anything like either one of us? Huh. Strange.”

I mean, have a look at the photo to the right (or below, depending on your media viewer). The kid is practically big enough to eat the parent. Yikes!

Image By Per Harald Olsen – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1887345

Researchers estimate that various cuckoo species have been practicing brood parasitism for around 60 million years. Wouldn’t one think that the flycatchers, warblers and buntings might have caught on by now? Apparently not. It’s a wonder they haven’t gone extinct.

But Not Our Guy

To be clear: the lousy parenting and “nestlings behaving badly” are the misdeeds of Old World cuckoos, along with the five cuckoo species in South America which are obligate brood parasites. Our own yellow-billed cuckoo here in North America typically — although not always — builds its own nest and raises its own young.

Image By lwolfartist – CC BY 2.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=125099464

(The US has its own obligate brood parasitic birds — chiefly the brown-headed cowbird — but we’ll save that for another time.)

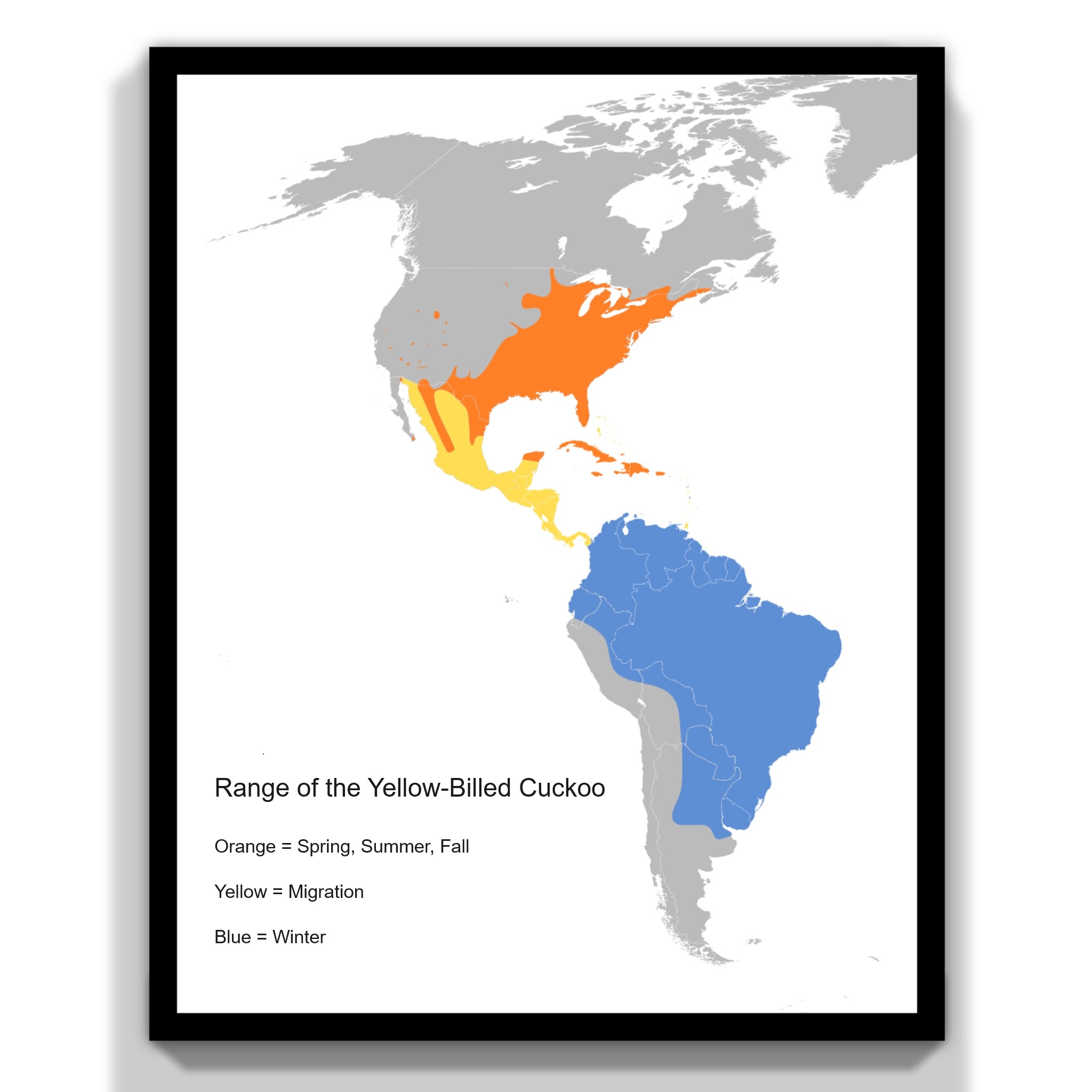

Geographic Range

Intercontinental travelers, the yellow-billed cuckoo spends late spring, summer and fall in Central and mostly North America for breeding and rearing their young, before heading to warmer climates for the winter. Peru and Bolivia seem to be their favored winter residences although some intrepid species members will fly as far south as Argentina.

Breeding grounds of the yellow-billed cuckoo once encompassed a wide swath of Central and North America, but have been drastically reduced in recent years. The decline has been particularly severe in the American West, where they have been reduced to fewer than 500 pairs. The bird is now nearly gone from most of its historical range across portions of 12 western states, with no recent sightings in Oregon, Washington, or Montana. Current range does include much of the US east of the Rocky Mountains, north to Canada and south to the Gulf Coast.

Image Courtesy of MAMMOTH CAVE AREA BIRDS

Catching a Glimpse

Observing the yellow-billed cuckoo in the wild is a challenge even for the most experienced bird watchers. They are notoriously secretive, generally quiet and tend to inhabit dense forest areas where their coloration allows them to blend in with ease. They also stand perfectly still for extended periods of time, both to avoid predators and to let their own prey (bugs and caterpillars) come to them.

Depicting Yellow-Billed Cuckoo

Look for yellow-billed cuckoos in thick woodlands and especially riparian habitats (areas along rivers, streams and wetlands — I had to look it up, too). These sorts of habitats provide the food sources and nesting sites they prefer. They can also be found in various forested regions, including deciduous forests, mixed forests, and woodland edges.

Look for them among the trees, especially in areas with a dense understory and a mix of shrubs, vines, and leafy vegetation.

When searching for yellow-billed cuckoos, it’s important to listen for their distinctive song. They don’t sing as much as a lot of other bird species, but you’re still much more likely to hear them than to see them. Patience and keen observation are key, as cuckoos can be secretive and well-camouflaged among the foliage. Using binoculars and familiarizing yourself with their vocalizations will greatly enhance your chances of spotting this fascinating but elusive bird.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

So there you have it: Part One of our piece on the yellow-billed cuckoo. Hope you’re enjoying it so far. We’ll have Part Two for you in a week or so.

By Steven Roberts