By Rhododendrites – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=103770921

Some folks love them. Some folks are…let’s just say “less enthusiastic.” However you may feel about them, there’s a whole lot to know about blue jays so grab your binoculars — or your favorite reading glasses — and let’s see what we can learn about the Cyanocitta cristata.

What’s With The Name?

The first half of the blue jay’s name has an obvious origin — the bright indigo coloration of most of their feathers. Except that’s wrong. Blue jays are not actually blue (neither are bluebirds or indigo buntings, for that matter). Yes, you read that correctly. And no, I am not making a joke.

Blue pigment is actually very rare in nature. The pigment in blue jay feathers is melanin, which is actually brown in color. So, have our eyes been deceiving us down through the centuries? Not exactly, although it is a sort of optical illusion. Similar to the workings of a prism, a process called light scattering makes the jays blue.

All birds feathers are composed of the protein beta-keratin. Blue jays, though, are somewhat unique in that their feathering contains miniscule air pockets. When light hits these air pockets, all the colors of the visible wavelengths except blue are absorbed.The blue wavelength is refracted which gives the birds their apparent coloration. Remember that song by Crystal Gayle back in the 1970s, “Don’t It Make My Brown Eyes Blue?” Well, I think someone needs to do a rewrite in honor of our masquerading feathered friends — “Don’t It Make My Brown Birds Blue?” Yes? OK, maybe not.

The “jay” part of the name is a little less complicated. Apparently some folks way back when thought that the bird’s call sounded like “Jay! Jay!” Personally, I think their ears deceived them even more than our eyes do with this bird, but let’s face it: No one asked me, and so “blue jay” it is.

That Nudity Thing

We’ve all heard the idiom, “naked as a jay bird.” It basically means a person’s apparel choices, are — shall we say? — somewhat minimalist. The expression’s been around for awhile and was a favorite of Mark Twain’s. It has nothing to do with actual birds.

Sure, you might find a few folks out there who claim that the blue jay chicks are naked when they hatch, so maybe there is a connection? And they can look rather shabby when they molt and maybe some of them lose almost all their feathers? No! Just, no. These people are bird brains. Nearly two-thirds of ALL bird species are born practically bald (the scientific term is altricial), and every bird molts. Good grief.

University of Pittsburgh, Public Domain,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8750874

Here’s the real story, or what I like to call “the non-alternative facts.” Starting in the mid-1800s, in American English a jailbird was a person imprisoned in a penitentiary institution of some sort. After some years, the language evolved and abbreviated it as j-bird. Now when an inmate checked in for their correctional sabbatical, they were stripped naked as part of the delousing process (Charming, right?). You can see where this is going. “Naked as a jay bird” may sound avian, but it’s actually penal.

OK. Moving right along…

Image By Jebbles CC0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=108088972

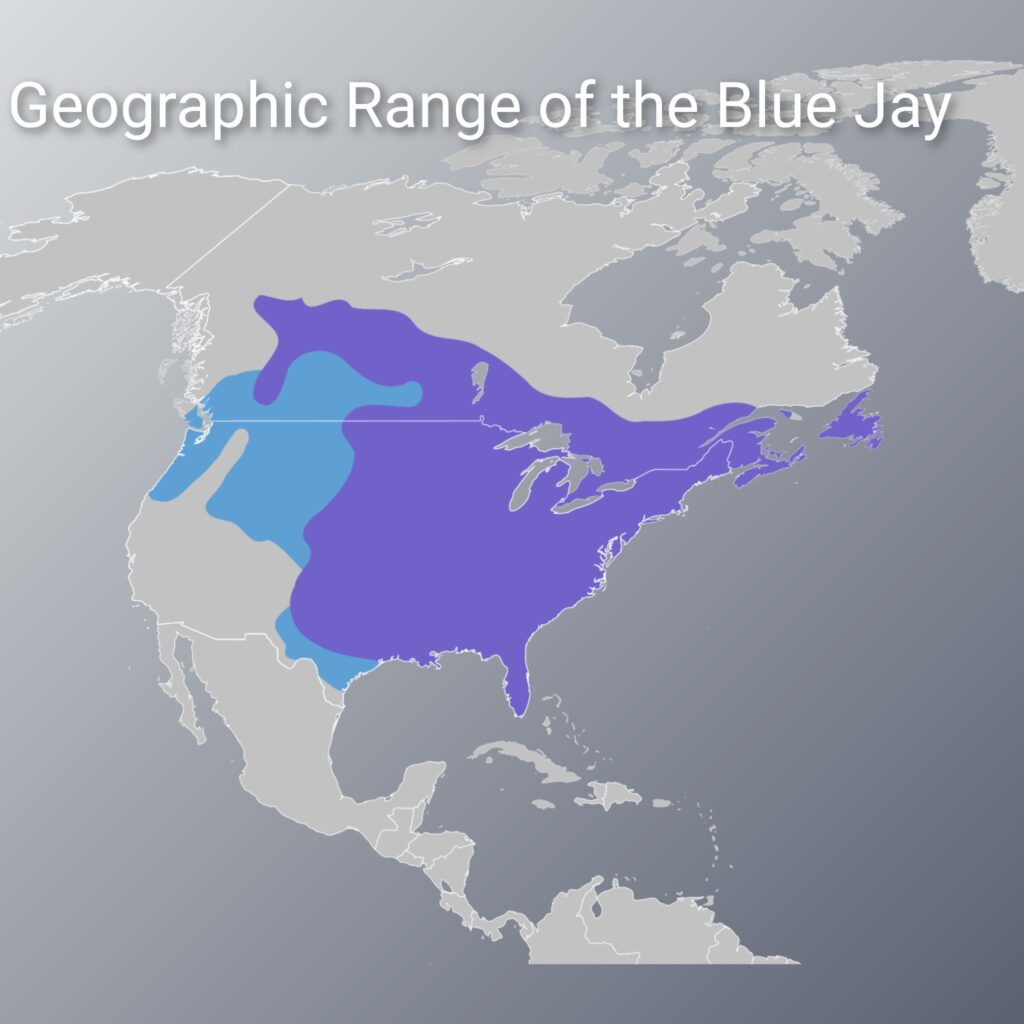

Geographic Range

The blue jay is strictly a North American resident where it occurs throughout the eastern and central U.S., as far south as Florida and west to Texas, as well as much of southern Canada west to the Rocky Mountains. This very adaptable species is even expanding its range into the Northwest in recent years. There are four recognized subspecies but only very subtle differences distinguish them from each other. They tend to avoid purely coniferous forests, preferring deciduous and mixed woodlands with a particular fondness for oak trees.

The Migration Mystery

Blue jays migrate. Except when they don’t. And when they do, some of them head in the wrong direction. The plain fact is that we actually don’t know that much about their migration habits. For many years it was thought that younger birds tended to migrate while their elders stayed put. Recent studies seemed to show the opposite. One theory was that colder weather patterns may have caused migrations that otherwise wouldn’t have happened. The slight problem with this theory is that no evidence supports it. Oh, well. A little mystery adds to the allure of this majestic creature, at least in my opinion.

Mating, Nesting and Rearing Behaviors

Blue Jays are monogamous birds that form strong pair bonds and mate for life. Mating season kicks off in late winter and early spring. The female constructs the nest from twigs, bark, grass, moss and weeds, often held together with mud. Nests are usually situated in the branches of trees at heights of anywhere from 10 to 30 feet.

Image By Jeff the quiet – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15306871

A typical clutch ranges from 3 to 7 eggs, and both parents share incubation duties. After 16-18 days, it’s hatching time, after which both parents provide nourishment and protection for about three weeks. After that, it’s fledging time when the youngsters learn the basics of flying while remaining in fairly close proximity to the nest for a few more weeks. The family unit stays together for another two to three months, with some observed instances actually being considerably longer.

The typical blue jay pair will have only one brood per mating season, especially in the northern reaches of their range. Those further south will occasionally do the deed twice each year. Some years they will nest in the same area as previous years, but other times they explore new horizons. We’re not sure why. It’s yet another glorious blue jay mystery.

Images from the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Public Domain,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=54300

Lifespan

The typical blue jay in the wild lives about seven years, though a significant percentage of them reach age 12. And depending on who you believe, the oldest blue jay on record was either 17 or 26 years, 11 months. These clever birds sure do an excellent job of keeping their secrets, don’t they?

How Big?

Adult blue jays are 10 to 12 inches, beak to tail. Being on the larger size compared to other backyard birds, they weigh in at 2.5 to 4 ounces. Their wingspans range from 13 to 17 inches. Males are usually ever-so-slightly larger than females, but not always. Natch.

For Their Dining Pleasure…

Blue jays are omnivorous and opportunistic feeders. Seeds, nuts, acorns, grains, corn, fruits, insects, lizards, rodents, frogs and small bats are all on the menu. So are other birds’ eggs and nestlings, at least occasionally. (Rude!)

Image By User: Saforrest – Own Work , CC BY-SA 3.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2962536

So About Their Misbehavior…

I hinted in the first paragraph that blue jays have some vociferous and adamant detractors. In fact, it started all the way back with the father of American birdwatching, John James Audubon. What did he have to say about it?

“Who could imagine,” Audubon pontificated, “So much mischief; — that selfishness, duplicity, and malice should form the moral accompaniments of…these gay deceivers.” Clearly not a big fan.

What’s more? Even that paragon of literary virtue, Atticus Finch, told his children “Shoot all the bluejays you want, if you can hit ’em.” Yikes. (Nowadays, of course, blue jays and all songbirds are protected by the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act and shooting them will land you in a heap of trouble.) And American writer and philosopher Henry David Thoreau referred to their characteristic call as an “unrelenting steel-cold scream.” Apparently he was not their greatest admirer, either.

Of course, some of their troubles are self-inflicted. If they visit your bird feeder, you’ve undoubtedly seen blue jays act like the bully on the playground. They can be loud and aggressive, threatening and physically attacking smaller birds. And let’s face it, given free rein at the feeder, they behave like pigs at the trough and will quickly take most of whatever’s on offer for their own purposes, leaving other birds nothing but empty shells and hulls. And if you’ve ever approached one of their nests, you probably experienced their free-for-all, raucous dive-bombing until you decided there were other pieces of real estate with a more appealing tranquility, and headed there. And we’ve already mentioned some of their less-than-savory meal-time choices.

More Weird Stuff

As common and well-known as the blue jay is, we’ve already established that there sure seems to be a lot that we do not know. Another example is their eccentric “anting” behavior. No, females don’t help look after their sibling’s children. That would be relatively normal. Oh, no. “Anting” is where a blue jay spreads its wings, tucks its tail between its legs, somewhat gently grabs an ant in its bill, rubs the ant through its feathers and then swallows it. Why? Could they just be messing with us? Probably not. Researchers are currently focused mainly on two theories. The first is that the ant’s formic acid serves as a type of parasite-repellent for lice and mites. The second is that rubbing the ants against themselves removes the extremely bitter aforementioned formic acid, which makes the ants palatable. Most birds won’t eat ants because of their horrible taste, but perhaps the clever blue jay has cracked the code?

But wait, there’s more. Blue jays in some specific geographic areas have developed a taste for household paint. Again, I jest not. Blue jays sometimes make like woodpeckers and chip light colored paint right off buildings. Then they proceed to collect it off the ground and store it until spring. That’s when they chow down on this very odd delicacy.

Affected homeowners eventually came up with a solution, which has given researchers a better idea of why this craziness happens. Leaving out a considerable volume of crushed eggshells near established bird feeders effectively tempted the birds away from their paint chip cuisine. It turns out that a considerable amount of limestone is used in making many lighter-colored house paints. What’s more, areas which experience high levels of acid rain show greatly depleted natural calcium levels in the soil. Calcium is a critical mineral for egg production in birds. And if you guessed that limestone would be an excellent alternative source of calcium, congratulations! You’re smart as a blue jay.

Image By Jim Ridley 2010. – Jim Ridley, CC BY-SA 4.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=61188145

Where To Look

Birdwatchers seeking blue jays should focus on wooded areas with oak or beech trees, as well as parks, woodlots and suburban neighborhoods with mature trees. They tend to prefer forest edges to deep forest, and will also frequent scrub brush areas, particularly if there are hazelnuts to be had. One significant advantage of this noisy bird for serious birdwatchers is that if there are any around, you’ll know it. Their loud, raucous behavior and striking coloration make them difficult to miss.

Invite Them Over To Your Place

Interested in attracting blue jays to your backyard? Here’s some ideas.

- Offer cracked corn, sunflower seeds and especially peanuts year-round at your bird feeder. As noted above, egg shells or other calcium supplements may also be a good idea in some areas. Suet provides concentrated fat and protein which gives a critical energy boost during winter months.

- Used large feeders and solidly anchor them to a pole or tree. Blue jays are relatively large backyard birds and like to have plenty of space to perch. They dislike the instability of smaller hanging feeders more suitable to chickadees or nuthatches.

- Provide a birdbath with three to five inches of water, heated in the winter if possible. Make sure to thoroughly clean and sanitize the birdbath at least several times weekly.

- Plant deciduous and nut-bearing trees and shrubs around your property. Oak and hazelnut are excellent choices.

- Most blue jays scorn traditional birdhouses, but will utilize larger nesting platforms. Place them under eaves or a sloping roof for protection. They will also typically accept nesting materials like dried grass or moss if offered.

- Scatter leaf litter (mulched leaves or dried grass clippings) around your yard. Blue jays cache their food under it for their later dining pleasure.

*********************************************

So there you have it. Blue jays are one of our most common backyard birds, and yet they maintain about themselves a certain air of mystery. Love ‘em or not love ‘em, they never fail to fascinate. And it always seems like there’s something more to learn about them.

By Steven Roberts