The Charming and Iconic Symbol of Upland Bird Hunting — Considered “The Prince of Game Birds — That’s Also a Favorite of Birdwatchers and Backyard Bird Enthusiasts

Image By Panza Rayada, CC BY-SA 3.0

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=58019928

Endearing, attractive, melodic, sociable — and now significantly declining in numbers — that’s Colinus virginianus, the northern bobwhite. Also called the Virginia Quail — and “Johnny Bob” in some parts of the American South — this well-camouflaged and somewhat secretive New World quail species is one of the most intensively studied bird species in the world, due to its history as a preeminent game bird. Scientists have researched the impacts of various human activities — from pesticide application to prescribed burning — on both wild and captive bobwhites. Let’s explore some of what we know.

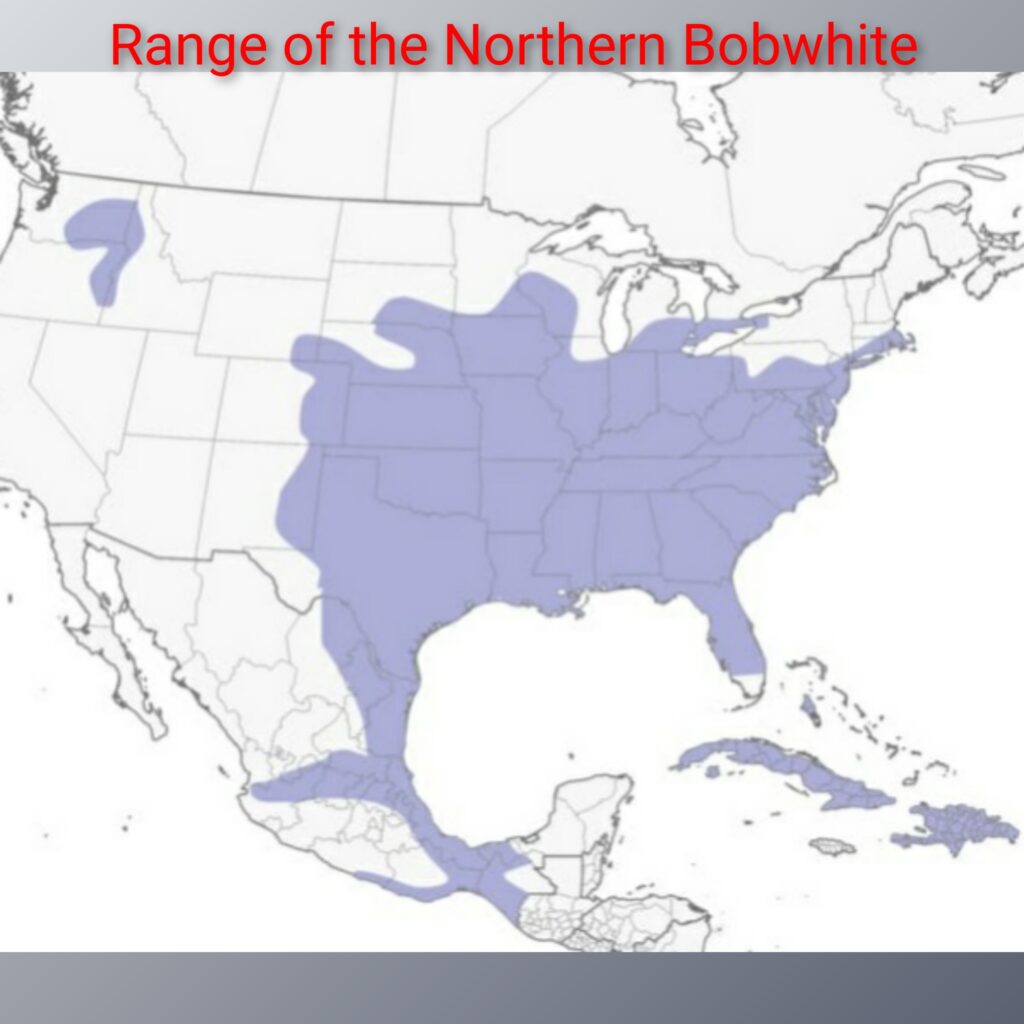

Geographic Range

The northern bobwhite is divided into a whopping 22 subspecies, which are primarily found in the eastern and central parts of the United States, ranging from southern Ontario and Quebec in Canada, through the eastern United States, and extending into parts of Mexico and Central America. Introduced populations have also been established on Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Bahamas.

Habitat Preferences

Although primarily associated with grasslands — and especially successional habitats (I’ll explain below) — the various northern bobwhite subspecies can be found in a variety of different environments:

Image By Cyndy Sims Parr – CC BY-SA 2.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20187408

- Early Successional Habitat: Bobwhites have a great fondness for early successional habitats, which are characterized by young, regenerating vegetation following disturbances such as fire, grazing, or timber harvest. These habitats provide a diverse mix of grasses, forbs, and shrubs at various stages of growth, offering ample cover, nesting sites, and food resources for bobwhites.

- Forbs: Bobwhites rely on a variety of forbs, which are herbaceous flowering plants, for their diet and cover. They prefer areas with a diverse array of forbs, including legumes, sunflowers, ragweed, pigweed, and smartweed. Forbs provide important food resources, including seeds, fruits, and insects.

- Grasslands: Bobwhites thrive in grassland habitats, including native prairies, old fields, and managed grasslands. They prefer areas with a mix of native grass species such as little bluestem, big bluestem, Indian grass, and switchgrass. These grasses provide cover and nesting sites for bobwhites.

Image By U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters – Public Domain

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20187336

- Shrubs and Brushy Cover: Bobwhites benefit from the presence of shrubs and brushy cover, which provide nesting sites, escape cover, and protection from predators. They are often associated with shrub species such as blackberry, sumac, dogwood, wild plum, and honeysuckle.

- Edge Habitats: Bobwhites are also found in habitats with a mixture of open areas and woody vegetation, such as field edges, forest clearings and ecotones between different habitat types. These edge habitats provide a transition zone with a mix of grasses, forbs and shrubs that bobwhites utilize for cover, nesting and foraging.

- Disturbance and Management: Bobwhites benefit from habitat disturbances that create and maintain early successional habitats. Natural disturbances like fire and grazing can help maintain suitable habitat conditions for bobwhites. However, in areas with agricultural landscapes, careful land management practices such as rotational grazing, prescribed burning and selective mowing or haying can help create and maintain suitable bobwhite habitat.

Named For Its Song

The northern bobwhite gets its name from the familiar and distinctive song which consists of a clear whistle that sounds (at least to some folks) like “bob-WHITE” or “bob-bob-WHITE.” And something being named after the sound it makes means I get to use one of my favorite words: Onomatopoeia! (Hope you enjoyed that as much as I did.)

The “bobwhite” call is typically performed by males looking for an interested female, or as a way of announcing their territory. The clear, distinct notes of the call are often repeated in a series that may vary in pitch, speed and pattern among individual birds. Each male bobwhite has its unique variation of the whistled call, which can help distinguish individuals and contribute to territorial recognition.

Here. Have a listen.

Image by By Dick Daniels – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=19230312

Female bobwhites also produce vocalizations, although their calls are typically less prominent and distinct compared to the whistled calls of males. Female vocalizations are often softer and more subdued, including clucks, chirps and soft whistles. These vocalizations are used for communication with mates, chicks and other members of the covey.

Bobwhites also have alarm calls that alert other birds to potential threats or predators. These alarm calls are usually sharp, loud and distinct, helping to warn other bobwhites of danger and prompt them to take cover.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=63155835

Raising A Family

Bobwhites will form pair bonds during the breeding season, but apparently some birds take the bond more seriously than others. Researchers using radio tracking of individuals recently found that both male and female bobwhites can have multiple mates in one season.

Mating typically occurs from late spring to early summer. Once a pair is formed, the male accompanies the female to suitable nesting sites, which are often located on the ground in dense vegetation or at the base of shrubs. The nest is a simple scrape lined with grasses and leaves.

The female lays a clutch of 10-12 eggs, which she incubates for about 24 days. After hatching, the chicks leave the nest within hours and are capable of feeding themselves. They grow rapidly and develop adult-like plumage within a few weeks. Both parents participate in caring for and protecting the brood until the young become independent.

What’s On the Menu?

Northern bobwhites are omnivores, consuming a variety of seeds, fruits, buds and sprouts, as well as insects, spiders, snails and other small invertebrates. In areas with agricultural fields, bobwhites often feed on grains and crops such as corn, soybeans, wheat and millet. Their varied diet allows them to adapt to different food sources based on availability.

So Do They Fly?

The northern bobwhite is certainly capable of flying but mostly chooses not to. Instead, they rely on their strong legs for walking and running, reserving flight for emergencies.

Image By ALAN SCHMIERER – CC0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=72429394

They spend much of their time foraging on the ground, scratching in the leaf litter, and walking or running rather than flying. The wing structure of bobwhite quails is adapted for their specific flight requirements. Their wings are relatively short and rounded, allowing for quick takeoffs and maneuverability in dense vegetation.

Group Outings

Except for the approximately two months of mating season each year when the adults pair off to breed, northern bobwhites can often be found in groupings of 10 to 25 birds known as coveys. Coveys are typically formed from summer through early fall, after the breeding season. During this time, birds from different family groups or broods come together to form larger social units. The coveys remain together throughout the fall and winter months, providing benefits such as increased foraging efficiency, protection from predators and social interaction.

Image By Andy Morffew, CC BY 2.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=61980396

Worrisome Decline In Numbers

On the conservation front, there are some problems — surprisingly big ones in fact.

The northern bobwhite has experienced substantial population declines across its range for more than half a century now. The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) collects data on bird populations. According to their extensive surveying and count, the overall trend for the northern bobwhite in the United States from 1966 to 2015 showed a significant decline of approximately 85%. That’s huge. That’s bad.

Similarly — according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service — the northern bobwhite has experienced a range-wide decline of about 4% per year from 1966 to 2014. This decline has resulted in the species being designated as a “Species of Greatest Conservation Need” in many states within its range. The northern bobwhite is rated as “near-threatened” species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

The Main Culprits

Avian researchers and conservation officials point to a number of complicated and wide-ranging issues that have negatively impacted bobwhite numbers. Chief among them are habitat loss and fragmentation, changes in land use practices, intensive agriculture, new and expanded pesticide use and increasingly limited genetic diversity among breeding populations. Unfortunately, there are no easy fixes for any of these complex challenges, and we’re running out of time.

Current conservation efforts for the northern bobwhite focus on preserving and restoring its habitat, improving land management practices, and raising awareness about its conservation needs. Initiatives include creating and managing native grasslands, shrublands, and early successional habitats that provide suitable nesting and foraging areas. Programs such as conservation easements and Farm Bill initiatives provide financial incentives and technical assistance to landowners for implementing habitat management practices. Collaborative partnerships and research programs contribute to monitoring bobwhite populations and informing adaptive conservation strategies. Public outreach and education campaigns aim to engage stakeholders in bobwhite conservation and promote actions to support habitat preservation. Let’s hope it’s enough.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

So there you have it. The northern bobwhite is a delight to hear and to behold. Long one of America’s most popular game birds, its population has dropped by near-shocking percentages over the last 60 years. Conservation efforts are being spearheaded by the National Bobwhite Technical Committee (NBTC). Comprised of over 100 wildlife professionals from state and federal agencies, universities, and private organizations — and based out of Clemson University in South Carolina — the NBTC is committed to saving these wonderful birds before it’s too late. If you would like to learn more about the NBTC efforts, their phone number is 502-680-3480 and their website is https://nbgi.org/

By Steven Roberts